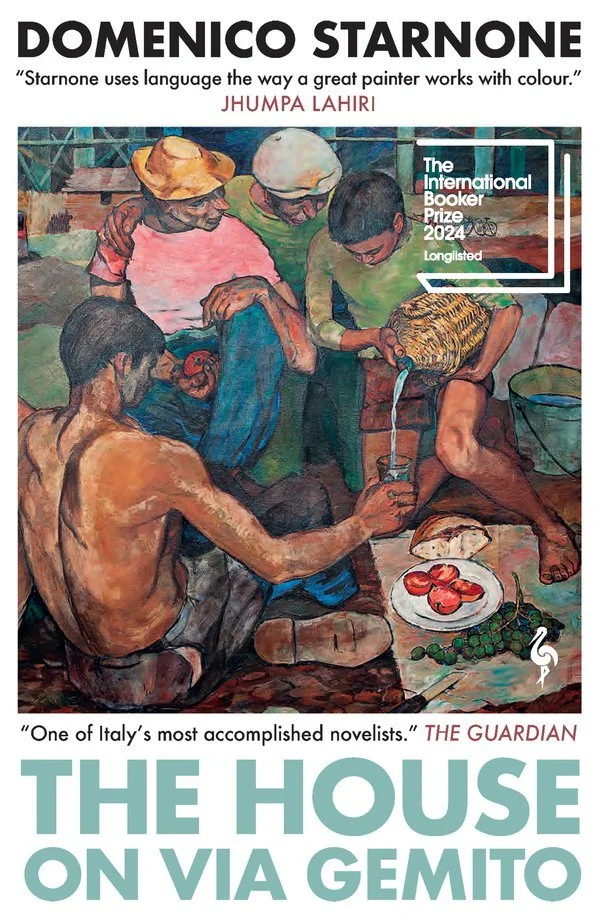

When a Parent's Inner World Becomes Your Cage:

Reflections on The House on Via Gemito by Domenico Starnone

Some novels don't just tell stories; they help us understand our own past more clearly, giving shape and language to experiences we may have lived through without fully naming them. Domenico Starnone's The House on Via Gemito is one of these works. It traces the particular suffocation that occurs when a parent's fragile grandiosity becomes the air everyone else must breathe.

The Story in Brief

Set in the gritty, vibrant streets of post-war Naples, The House on Via Gemito is a fictionalised memoir centered on the narrator’s father, Federí. A railway clerk by day and a frustrated painter by night, Federí is a man consumed by the belief that he is a genius thwarted by circumstance. The novel follows the adult narrator, Mimì, as he attempts to reconstruct the truth of his childhood from beneath the heavy shadow of his father’s lies, violent outbursts, and relentless self-mythologizing. It is a story about the cost of living with a man who demands to be the sun around which the entire family orbits.

The Father Who Takes Up All the Space

Federí isn’t the cartoon villain we sometimes imagine when we hear the word narcissism. He is a wounded, disappointed man who genuinely believes he was meant for a different life. His talent as a painter becomes proof, in his mind, that he was destined for something greater. When that future never arrives, the gap between who he thinks he should have been and who he actually is turns into something the whole family has to live with.

Starnone captures the quietness of this kind of narcissistic control. There are no big scenes or shocking moments. Instead, the family home slowly rearranges itself around one person’s emotional needs. The father’s version of events becomes the only one that feels safe to accept. Questioning him, even gently, carries a sense of risk.

This is the kind of narcissism I see most often in my work. It is not loud or flamboyant. It seeps into daily life and shapes the atmosphere of the home in subtle ways. What makes it harmful is not only how little space it leaves for anyone else, but how unaware people often are that this is happening. Children slowly adjust their feelings, actions and expectations around the narcissistic parent without realising they are doing it. Over time, this survival strategy erodes their sense of self. The coping mechanisms they learn begin to shape their personality and development: they become the one who keeps the peace, avoids conflict, stays small, or fulfils the role the narcissistic parent has assigned to them. Many reach adulthood believing that this role is who they truly are.

It is important to note that Federí’s behavior is not just a clinical vacuum; it is deeply rooted in post-WWII Neapolitan culture. His grandiosity is fuelled by a specific brand of Mediterranean patriarchy and a strong sense of being held back by his social class. He is a man who feels "belittled" by his job as a railway clerk, and his narcissism acts as a defence mechanism against a society that refuses to see him as the great artist he believes himself to be.

Growing Up Inside Someone Else's Story

Mimì, the narrator, spends his childhood and beyond trying to understand what was real and what was shaped by his father’s storytelling. His memories feel blurred and unreliable after years of hearing his father’s exaggerated versions of events. Over time, his own understanding of what happened is shaped and defined by his father’s account, making it hard for him to trust his own perception at all.

This is what happens when you grow up with a narcissistic parent: your own inner life becomes uncertain. Your feelings and memories never fully “count” because they can be dismissed, corrected, or replaced by the parent’s version. Their need to be right takes priority over your need to make sense of your own experience.

The work of adulthood, then, becomes archaeological. You're excavating your own experience from beneath layers of someone else's narrative. Therapy can help with this work, allowing you to trust what you truly felt, rather than what you were told you were feeling.

The Fragility Beneath the Grandiosity

Starnone shows that Federí’s self-importance is not real confidence. It is a defence. Beneath the grand talk and the big claims is a deep shame he cannot face: the fear of being ordinary, the fear of having failed, the fear of not mattering. His grandiosity exists to cover that wound.

This is often the core of narcissism. The self-image is so fragile that it has to be protected at all times, and the family ends up carrying the weight of that protection. Everyone learns to support the parent’s version of themselves, because if that image collapses, the parent collapses with it.

Growing up around this kind of emotional fragility is draining. Children learn to monitor every shift in mood. They walk into rooms already scanning for tension. They grow up too quickly, not because they were encouraged to mature, but because they had to manage a parent’s emotional state long before they understood their own. By the time they reach adulthood, many have become experts at taking care of others while having very little practice in taking care of themselves.

The Mother as Quiet Regulator: When Protection Becomes Enabling

While Federí dominates the emotional life of the family, Mimì’s mother takes on the role of managing the damage. She absorbs his volatility, protects the children where she can, and tries to create some sense of stability in a household shaped by his moods. She neither openly supports nor openly challenges the father’s version of reality. Instead, she manages the consequences of it.

This is where the novel touches on something many adult children of narcissistic parents struggle to articulate: the role of the enabler. The parent who is not overtly abusive, but who keeps the family functioning by staying silent. This parent often feels safer or more predictable than the narcissistic one, but that does not mean they are more emotionally present. In many families, the enabler is emotionally unavailable because all their energy is spent managing, calming, or anticipating the narcissist’s behaviour. There is little left for the children.

Starnone portrays the enabler in this way. Mimì’s mother sees what is happening. She understands the fragility beneath Federí’s grandiosity and knows that confronting him would escalate conflict, with the children bearing the consequences. Her enabling is not rooted in believing his self-image, but in trying to limit harm. At the same time, the cost of this role is emotional distance. She becomes focused on maintaining stability rather than connecting with her children. They may be shielded from the worst of the father’s behaviour, but they are not fully met or emotionally held, because the parent who might have done that is exhausted by the work of containing the narcissist.

But this strategy comes with a hidden consequence. By absorbing the father’s moods without naming them, and by building stability around his instability, she unintentionally teaches the children that this dynamic is normal. That one person’s emotional needs can sit at the centre of the family. That love means adapting and accommodating, not being seen.

Over time, this becomes a template for survival. You do not confront. You do not question. You adjust yourself instead. For Mimì, this lack of validation becomes part of his internal world. It deepens his confusion about what is real, what is exaggerated, and what belongs to him. The mother reduces immediate harm while also helping to sustain the conditions in which psychological harm becomes familiar.

Many clients recognise this pattern instantly. One parent creates tension. The other smooths it over. The child grows up loving both, yet living in two different emotional worlds. And the anger that cannot be directed at the narcissistic parent often lands on the enabler instead, because she was the one who could have stepped in and did not, or could not, or did not feel able to.

The Children's Roles Within the System

Within this emotional structure, each child is shaped by the father’s needs and the mother’s ways of coping. Although Starnone does not reduce his characters to archetypes, the family dynamics closely resemble what is often seen in narcissistic families. Children adapt themselves in different ways depending on what the dominant parent needs in order to feel stable.

Mimì occupies an uncomfortable position between identification and resistance. He is drawn to his father and deeply affected by him, yet also wounded by his presence. He is both drawn to his father and wounded by him. He becomes the sensitive, observant child who tries to make sense of contradictions that no one explains. This places him in a position similar to what is sometimes called the "parentified witness": a child who carries the psychological truth of the family without the power to articulate it. He is not the father's chosen heir, yet he is deeply shaped by the father's emotional gravity.

Other children adapt in different ways. One becomes more compliant, learning early that agreement and accommodation reduce tension. This child keeps things running smoothly by not challenging the father’s version of reality. Their role is stabilising. By staying aligned or neutral, they experience fewer emotional outbursts. In many families, this role evolves into a version of the "golden child": the one who mirrors back admiration or neutrality and who confirms the parent's self-image simply by not conflicting with it.

There is also the child who reacts differently. This child becomes more openly distressed, angry, or resistant. By not fitting neatly into the family’s unspoken rules, they expose what is wrong. Their behaviour reflects the strain in the system, which the narcissistic parent cannot tolerate. As a result, they often become the focus of blame or criticism, carrying the family’s unacknowledged tension. This is the child who later recognises themselves as the scapegoat or black sheep, not because they are inherently difficult, but because they refuse or fail to adapt convincingly.

These roles are fluid rather than fixed. Starnone portrays them as responses to evolving family pressures rather than as permanent identities. What matters is that each child adapts to the father's emotional demands in different ways, and these adaptations shape their later sense of self. The family becomes an ecosystem organised around the father's fragility, with the mother working behind the scenes to keep the system operational.

The result is a family system that orbits around a single centre. The father's inner world sets the tone for the household. The mother's silence and vigilance keep the atmosphere from collapsing. The children absorb roles that keep the system functioning, even though that functioning comes at the cost of clarity and self-trust.

No one in the family explicitly names these dynamics. The dynamics are lived rather than named. This is why the novel feels so psychologically accurate. Narcissistic families rarely revolve around dramatic confrontations. More often, they create a slow erosion of self-perception. Children learn to read emotional shifts, anticipate moods, and adapt themselves to someone whose sense of self cannot tolerate challenge. The mother understands more than she says. The children sense more than they can articulate. The father remains largely unaware of the emotional cost of his presence.

Memory as a Contested Territory

One of the novel's most powerful elements is Mimì's struggle with memory itself. He circles back repeatedly to the same events, questioning whether what he remembers actually happened or whether his memories have been shaped by his father's endless retellings. The confusion is not just about the events themselves. It is about whether he can trust his own mind at all.

When you grow up in a narcissistic family system, memory becomes unreliable not because your brain fails you, but because the family narrative actively rewrites what happened. The narcissistic parent insists on their version. The enabling parent doesn't contradict it. And you, the child, learn that your clearest recollections can be dismissed as misunderstandings, exaggerations, or fabrications.

This is a very familiar experience for adult children of narcissistic or emotionally immature parents. When they confront the parent about what happened, they are almost always met with denial, blame, or gaslighting. The past is rewritten to protect the parent, and the child is left questioning their own memory all over again.

This is gaslighting in its most insidious form: It isn’t one dramatic incident, but the steady pressure of having your reality dismissed again and again. Over time, you start asking yourself the same question on repeat: “Did that really happen?”

In therapy, we often understand contested memory as an injured part of the self. When memory has been denied or rewritten for years, the past does not stay in the past. It remains active, easily triggered, and difficult to trust. The focus of therapy is not to force certainty, but to soothe the confusion, help the person ground themselves in the present, and gradually rebuild a sense of internal safety. As this injured part is attended to rather than questioned, memories begin to feel less overwhelming, and the person can relate to their past without being pulled back into it.

What This Novel Offers Those Who Recognise Themselves

If you grew up with a narcissistic parent, parts of this story may feel uncomfortably familiar. The harm does not arrive all at once. It builds over time. A sense of self becomes uncertain. Holding onto your own perspective becomes difficult when another voice has always dominated the space.

Starnone does not pathologise or moralise these dynamics. He simply observes them. In doing so, he gives language to experiences that are hard to describe precisely because they were woven into ordinary family life rather than marked by obvious abuse.

The damage is rarely dramatic. It shows up in the loss of trust in your own mind, in growing up too quickly as you manage the emotional needs of adults, and in the loneliness of loving a parent who cannot fully see you because they are absorbed in maintaining their own self-image.

These patterns create a family system where survival depends on silence and constant adjustment to the narcissistic parent. Starnone allows this to unfold without judgement, which is what makes it so recognisable.

The Existential Question at the Heart of It All

Beyond the psychological dynamics, there's a deeper question here: how do you become yourself when you were raised inside someone else's story?

This is existential work. It's about reclaiming authorship over your own life. It's about recognising that you don't have to organise yourself around another person's fragility. That your existence doesn't require constant justification. That you have a right to your own inner life, your own memories, your own interpretation of what happened.

In existential terms, it's about moving from an existence defined by another's gaze to one grounded in your own being. From living as a character in someone else's narrative to becoming the author of your own.

In therapy, this is often where the real work begins, not in understanding what happened, but in choosing who you want to become now that you're no longer captive to someone else's narrative. It's about learning that you can hold complexity: that your parents were both the people who harmed you and the people you loved. That the enabling parent's failure to protect you doesn't erase the moments when she did offer comfort. That recognising the damage doesn't require you to hate anyone.

A Mirror, Not a Solution

The novel doesn't offer neat resolutions, and neither does the therapeutic process. Disentangling from a narcissistic parent's influence is slow, careful work. It requires patience with yourself as you learn to trust your own perceptions again. As you rebuild the parts of yourself that were pushed aside to make room for someone else.

There's grief in this work too. Grief for the childhood you didn't have. For the parent who couldn't see you. For the other parent who didn't intervene. For the years you spent believing the problem was you.

If you've recognised yourself in these dynamics, know that the uncertainty you feel about your own experience isn't weakness: it's evidence of what you survived. The doubt you carry is a rational response to having your reality systematically undermined. It is a normal response to an abnormal dynamic. And therapy can offer a space to reconstruct what was always yours: your own story, told in your own voice, with your own authority.

If you are dealing with the impact of growing up with a narcissistic or emotionally immature parent, I offer therapy that takes these experiences seriously. I work with clients in Blackheath, Southeast London, and online across the UK.